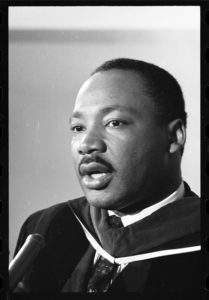

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. died 50 years ago this past week, which makes this an appropriate time to consider why he has a national holiday named after him, and you and I don’t.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. died 50 years ago this past week, which makes this an appropriate time to consider why he has a national holiday named after him, and you and I don’t.

Here are four of many reasons.

He sacrificed for his ideals. Everyone thinks they’re persecuted these days. King really was. There’s a reason his most famous writing was titled “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” He was in jail when he wrote it. While he’s been elevated to American sainthood since his death, 63 percent of respondents in a 1966 Gallup poll had a negative opinion of him (and only 12 percent a highly favorable one). Many saw him as an agitator. The FBI investigated him as a communist back when that accusation carried serious implications.

Listening to his sermon in Memphis the night before he died, it’s clear he believed he would not live long, which is understandable. He’d been stabbed in Harlem and struck in the head by a rock in Chicago. The physical strains of leading his movement must have been life-threatening. “I have seen the Promised Land,” he said in Memphis. “I may not get there with you.” He was right. He was shot the next day at age 39.

He didn’t cede the moral high ground. Rarely in a political debate is one side so right and the other so wrong as in King’s fight for racial equality.

So what do you do when you’re right? Sadly, some movements – including ones that have the moral high ground – resort to low-ground tactics. They play the political game, justifying their hardball, scorched-earth tactics by saying it’s the only way they can win, and besides, the other side deserves it. Plus they make a good living that way. In the process, they become indistinguishable from the status quo they’re trying to replace.

Contrast that with King’s philosophy. A movement for the powerless gained power by letting its oppressors abuse theirs. Has there been another Christian-based social movement in the past 100 years that has been more impactful – earthly, politically, I mean – than the civil rights movement? King’s movement didn’t advance in spite of following Jesus’ teachings to love your enemy and turn the other cheek. It advanced BECAUSE it did.

He offered hope. So much of today’s discourse is based on self-justifying, gloom-and-doom predictions and prophecies. It fuels outrage, fills seats and drives ratings, but it doesn’t inspire the masses to noble effort or sacrifice. No one marches in a parade led by a pessimist.

Compare that climate to King’s words: “We shall overcome because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” “I believe that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word in reality.” “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

That’s how you get people to risk things.

Finally, there’s this inescapable reason King has his own holiday. He died young. King’s death made him a mythical martyr who now is safe for any mainstream political figure to reference. We remember mostly “I have a dream,” and who can disagree with that? In reality, King stepped on a lot of toes calling for both racial and economic equality and opposing the Vietnam War. Some African-Americans were growing impatient with his nonviolent tactics.

Had he lived, King the man would not be so universally beloved as King the myth is. His reputation would have been bruised and battered, like all public figures’. Private failings would have become part of his public image. Specific political fights would have detracted from his overall message. What would he have said about Black Lives Matter or the NFL anthem protests? Regardless, he would have offended a lot of people.

A Gallup poll in 2011 found that 94 percent of Americans had a favorable opinion of him, and 69 percent a highly favorable one.

His death at age 39 helped make that possible. Now he belongs to all of us, or most of us.

For him, it meant he never made it to the Promised Land – the one on earth, anyway. But unlike many of us then and now, at least he saw it.

By Steve Brawner, © 2018 by Steve Brawner Communications, Inc.