By Steve Brawner

© 2015 by Steve Brawner Communications, Inc.

Faulkner County is the home of three degree-granting educational institutions – the University of Central Arkansas, Hendrix College, and Central Baptist College. Soon there will be a fourth – Greenbrier High School.

Twenty minutes north of Conway, the district is waiting final accreditation – and there’s no reason to believe it won’t be granted – from the Higher Learning Commission in Chicago. If that happens before the end of the school year, 8-10 students will graduate high school with a two-year associate’s degree from the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

Students already can earn college credit by taking concurrent and Advanced Placement courses – in other words, college English that counts as a high school English class. The cost for them and their families? Fifty dollars per class to give them “a little bit of skin in the game,” said Scott Spainour, the district’s superintendent, unless they can’t afford it, in which case it’s free. Lakeside High School in Garland County is partnering with National Park Community College to offer a similar opportunity.

Spainhour hopes the idea spreads beyond these two school districts. Arkansas ranks 49th in the country, above only West Virginia, in its percentage of adults above age 25 with a bachelor’s degree. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 18.9 percent of Arkansans have reached that level of attainment.

Of course, having a four-year college degree isn’t necessary to be successful in life or to have a good-paying job – a fact that can be covered in another column. But, on average, you’re better off with more education than you are with less. The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco reported last year that average college graduates earn $830,800 more over their lifetimes than high school graduates. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the unemployment rate in 2013 was 7.5 percent for Americans with a high school diploma but 5.4 percent for those with an associate’s degree and 4 percent for those with a bachelor’s degree.

College, obviously, is expensive, even with all the scholarships available. Last year, Greenbrier graduates saved almost $700,000 in college tuition costs because they had already taken those courses in high school.

But cost alone is not the only barrier to college completion. Many students graduate high school unprepared academically, and only one in 10 students requiring remediation will graduate with a four-year degree, according to “Four-Year Myth,” a 2014 report by Complete College America. Meanwhile, a college education is a major disruption occurring in an unfamiliar environment during a transitory stage in life. According to Complete College America, only one advisor is available for every 400 students on a typical college campus. It’s no wonder the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center reported in 2014 that, during the last 20 years, 31 million college students have started school but not earned a degree.

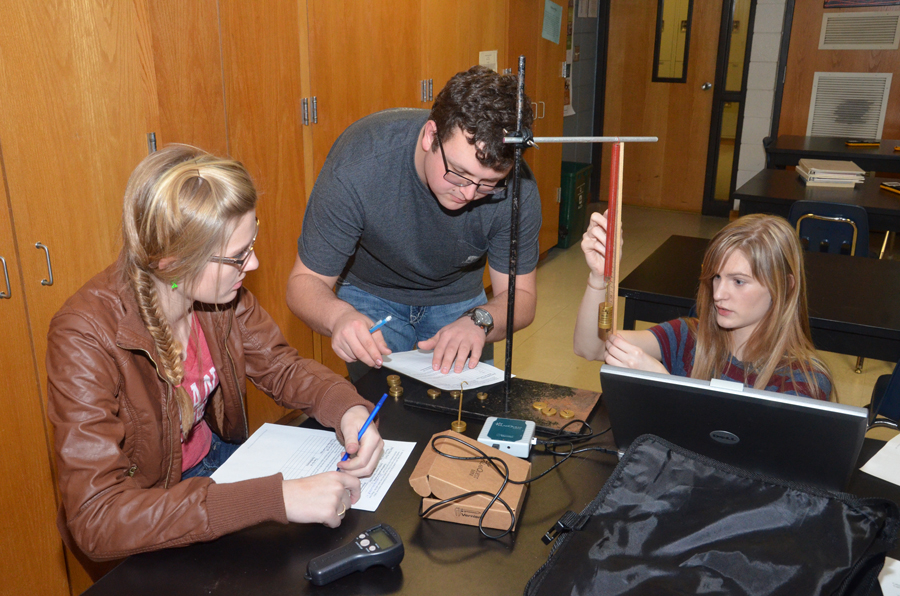

Students in Greenbrier and Lakeside, in contrast, will earn their hours in a familiar, supportive home environment before they go to college. “Four-Year Myth” reported that 62 percent of associate’s degree seekers who earn 30 credits during their first year graduate, compared with 10 percent with less than 12 credits. Greenbrier and Lakeside students easily can reach that level, and none of them have to be remediated. With up to two years of rigorous instruction already under their belts, they’re more likely to complete a four-year degree rather than drop out. And even if they enter the workforce straight from high school, they will be more job-ready because of the classes they have taken.

Arkansas has taken a number of steps to increase students’ educational attainment, including state-sponsored gambling through the lottery.

But making college more affordable isn’t enough. It’s not a good strategy to send 18-year-olds to a sprawling, impersonal campus and expect most of them to be successful. Arkansas has 297 public high schools, including Greenbrier and Lakeside, where classroom teachers know their students’ names and care about their well-being. There’s no reason many students can’t graduate with their basics at age 18, ready for more. Community colleges and four-year schools then can serve as economic and academic engines, not remedial facilities.

If this spreads – and it will – students could go “off to college” each morning from their homes, where parents can guide them, without going into debt. Sure seems like a better way to me.

Steve … What’s your prediction for the future of the traditional brick and mortar university? … I.e. Why do colleges (like our alma mater) continue to pour money into new structures when students are more and more turning to online learning and alternatives like you mention here?

Hi, Lance. I’ll respond, but only if you’ll offer your two cents as well.

The traditional university has to be a place where students are trained in a hands-on way for specific needs in the workplace – not a place to have the “college experience” and to broaden one’s mind.

You’re seeing that now, particularly in the community colleges that offer a lot of non-degree technical certificates. At Northwest Arkansas Community College in Bentonville, students learn how to operate a propriety software used by Walmart and its suppliers. They don’t earn academic credit, but they graduate the program in about 8-10 months with a job offer. The University of Arkansas at Fort Smith is a four-year school that works closely with local industry. The UA is distancing itself from the rest of the field by giving students real-world opportunities to learn entrepreneurial skills – not just going to class, but starting businesses while networking with the state’s leaders.

OBU? It’s been a long time since we’ve been there, so maybe it has evolved. But if it is what it was when we were there, it’s going to be less and less relevant. A liberal arts education by itself just isn’t going to cut it any more.

Your thoughts?

This is great news, Steve. Sounds like a way better system for starting one’s college experience than I had 41 years ago when I drove 550 miles to attend Harding University when I had spent very few nights away from my parents.

I’m hopeful, Ken.